Lessons from the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in 1902

Peter Drucker’s General Advice About Strategy for a NFP

Peter Drucker wrote in Managing the Nonprofit Organization:

There’s an old saying that good intentions don’t move mountains, bulldozers too. In nonprofit management, the mission and the plan – if that is all there is – are good intentions. Strategies are the bulldozers.

They convert what you want to do into accomplishment. They are particularly important in nonprofit organizations. Strategies lead you to work for results. They convert what you want to do into accomplishment. They also tell you what you need to have by the way of resources and people to get the results.

Peter Drucker, Managing the Nonprofit Organization [2].

Lazy Workers in Southern States – The View in 1902

The quote above from Peter Drucker is inspirational, but not particularly helpful for those broadly familiar with strategy and analytics. In this post, we look at a data driven strategy developed by John D. Rockefeller and those around him to improve living conditions and worker productivity in southern US states at the turn of the 20th Century. We follow [3] and [4].

The story begins with the US Public Health scientist Charles Stiles who identified diseases caused by hookworms (Necator americanus) as prevalent in Southern states, especially on farms and plantations in sandy areas. Hookworms are parasites, and those infected with them were anemic and had difficulty working [3]. To outsiders, workers infected with hookworms appeared to be lazy.

Stiles lectured on his investigations at a 1902 Sanitary Conference meeting in Washington and his findings were reported in newspapers, such as the New York Sun, which used the headline “Germ of Laziness Found [3].”

European physicians by the mid 1870’s linked the parasitic worms to human symptoms of severe anemia, pallor, and weakness [3]. Hookworms could enter through the souls of your feet, infect your body, were passed in your stools, returned to the ground, and could then infect others.

Rockefeller Sanitary Commission

In 1909, Stiles attracted the attention of John D. Rockefeller, who was by then a philanthropist, and Rockefeller provided $1 million (equivalent to about $27 million in 2021) to establish the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease. Rockefeller hired Stiles and project administrators [3].

The conditions in the Southern US were conducive to the spread of hookworm disease. As summarized in [3]: “Primitive living standards increased Black and White farm families’ vulnerability to disease. The risk of exposure to hookworm infection was great as well; John A. Ferrell noted that in the Southern rural sections, ‘open privies and, far too often, no privies at all, are used, [so that] millions upon millions of [hookworm] eggs are scattered over the earth, and develop into minute, infecting worms ready to attack.’ … The climate favored wide regional geographic distribution of hookworm as the land, marked by warmth, moisture, and aerated sandy or loamy soils, allowed hookworm larvae to burrow for protection from the sun, perhaps for years. Hookworm also was endemic in the mining towns of North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia, where the parasite found protection in mines from extremes of temperature and dryness [3].

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission [RSC] developed and executed a three prong strategy over the years 1909-1914:

- estimate hookworm prevalence in the American South;

- provide treatment;

- and eradicate the disease.

The RSC surveyed populations in 11 Southern states and found that about 40% of the population surveyed were infected with hookworms. Hookworms are still a problem today, with 500 million to 750 million individuals around the world estimated to be infected.

Reducing the prevalence of hookworm required understanding how it was spread:

Human transmission occurred as newly hatched hookworm larvae from eggs in contaminated soils entered hosts via direct, physical contact through a foot or hand. After penetrating the skin, they traveled to the heart and lungs and then to the small intestine, where they attached to capillaries to feed, remaining from 2 to 13 years. Females released thousands of eggs per day (9000–25000) into the intestine, which, after expulsion from the human body into inadequately designed privies or moist dirt, hatched in the soil and waited to enter human hosts, thus completing the cycle [3].

A campaign to educate people about the disease and how it was spread and to install latrines and toilets dramatically reduced the prevalence of the disease [3].

Three Lessons for Data Driven Not for Profits

The RSC was remarkably effective and there are many lessons that can be learned from it. Here we focus on just three.

Lesson 1. Use data to identify the problem and inform a solution. The RSC first surveyed the southern states to understand the problem and how best to deploy their resources. A large part of the effort was to collect appropriate data in order to develop an appropriate solution. Note that they did not rely on third party data from others, but funded efforts to collect the data that was needed.

Lesson 2. Make sure you understand the root cause of the problem so that appropriate actions can be taken. Here the actions was not just treating the disease, but even more important was understanding that the root cause of the disease was poor sanitary conditions that enabled the parasite to spread, and encouraging the use of latrines and toilets to stop the spread of the disease.

Lesson 3. Look at the problem holistically and deploy your funds to attack the problem as a whole. The RSC split their $1M of funding between i) research into the problem, ii) actions to treat patients and improve living conditions, and iii) education to change people’s behavior.

References

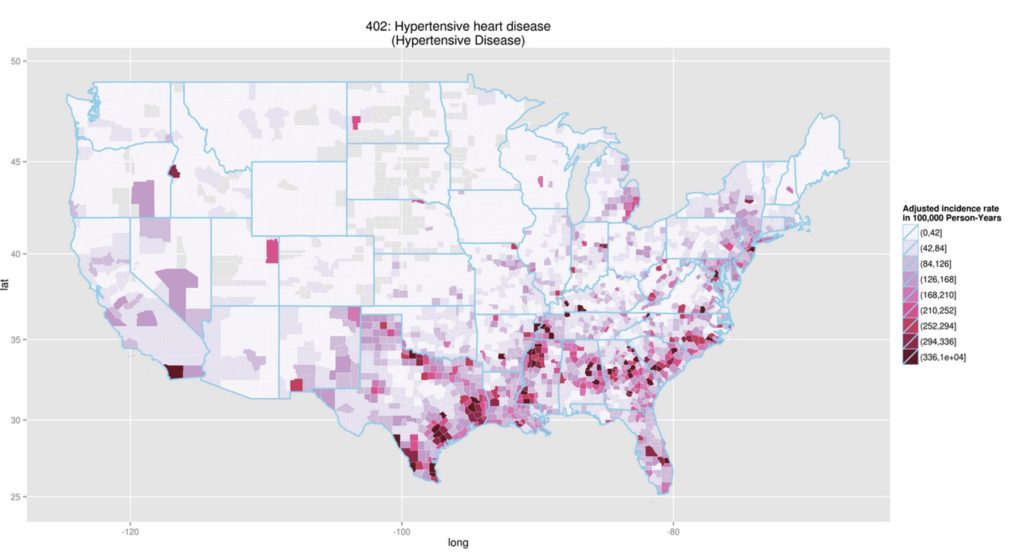

[1] Patterson, Maria T., and Robert L. Grossman. “Detecting spatial patterns of disease in large collections of electronic medical records using neighbor-based bootstrapping.” Big data 5, no. 3 (2017): 213-224.

[2] Drucker, Peter. Managing the non-profit organization. Routledge, 2012. Chapter 2.

[3] Elman, Cheryl, Robert A. McGuire, and Barbara Wittman. “Extending public health: the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and hookworm in the American south.” American journal of public health 104, no. 1 (2014): 47-58.

[4] Bleakley, Hoyt. “Disease and development: evidence from hookworm eradication in the American South.” The quarterly journal of economics 122, no. 1 (2007): 73-117.